Conference: Heritage, Community, Archives: Methods, Case Studies, Collaboration, Sheffield Hallam University

12–13 Jun 2023

Informed By

Leeds University

Special Collections, Leeds University

53.80792529298425,-1.5533825598282816

Heavy Water

Disused Quarry

53.190859190203106,-1.5886838699461436

Charms and Chasms

G39, Cardiff

51.48600889999999,-3.1646778

Charms and Chasms

Cardiff University Special Collections

51.49010149999999,-3.1821835

Material Rituals

Sheffield General Cemetery

53.3686665,-1.4859551

Heavy Water

Welbeck Estate

53.259282,-1.170231

Heavy Water

Bloc Studio

53.37464905135222,-1.4716190191185086

Abstract

The Heavy Water Collective presents artistic methods that agitate, deconstruct and reconfigure histories, using archives and collections as source material. Our objective is to construct a subversive archive of visual matter that critiques and destabilises established narratives, through direct engagements with historical artefacts and documents. We interrogate collections situated in university libraries, private estates and public archives across the United Kingdom, through an established artistic research methodology. We aim to construct a constellation of objects and subject matter, in a way that begins to incorporate these reconfigurations of the past into a re-reading of the present moment. Through an integration of stories, imaginings, perspectives and becomings, this artistic research project reflects upon the contemporary issues burgeoning out of the social, political and cultural strata examined.

In this presentation, we ask if new futures can be imagined through artistic practice when the past is radically reinterpreted. We explore how we might fill the absences in a collection through creative interpretation, using a rhizomatic approach to engaging with archives. Disregarding established categorisation within a collection reveals further insight as, for example, articulations of War sit alongside accounts of colonialist exploration, and patriarchal midwifery practices are aligned with violent witch-hunting methods. Forming networks of meaning through the subjects selected and the artworks produced, the Heavy Water Collective seeks to create a space in which established systems are destabilised and rituals of mourning are revered. The Heavy Water Collective brings an ethics of care with their scrutiny. Can empathy grow out of the material encountered? Can power and agency be redistributed through these artistic responses? Through this project, individual archives and collections become entangled, objects become ensnared and histories adopt a‑temporal qualities.

Generating New Sediment: Artistic Responses to Archives and Collections

There is a long history of artists working with archives. Monumental works, such as Fred Wilson’s Mining the Museum (1992) and Susan Hiller’s From the Freud Museum (1991−96), have influenced a generation of artists seeking to work with archival artefacts and collections in order to make sense of their contemporary context. There is something important about looking back, specifically in a context in which the future is uncertain. Artists who perhaps represent a struggle to redefine historical narratives — those narratives that exclude, neglect and misinterpret intersectional notions of identity — are at the forefront of this growing field of artistic research. Yet, as the climate crisis looms heavy on the global psyche, it is also a time in which looking back and making sense of how we got here has become, for many, a way in which to maintain some semblance of hope for the future. It is through this burgeoning of empathy for unearthed sorrows and a reconstitution of meaning in the context of 21st Century chaos that we find the Heavy Water Collective.

The Heavy Water Collective respond to objects and documents that relate to historic moments of turbulence. Accounts of war, depictions of imperialist colonisation, the subjugation of women, the erasure of indigenous cultures and the exploitation of natural resources — extracted from archives and collections across the UK — all speak of violent displacements in relation to social, cultural, political and environmental stratum. The growing threat of the unfolding environmental crisis, in itself a direct result of many of the historical activities and injustices referenced in the work, weaves through every aspect of contemporary society. We are living in post-natural times; an age of mass ecocides, species extinctions and post-natural disasters. In a political scramble to maintain capitalist growth in this depleting environment, we are also witnessing an increase in socio-political crises. In Britain, for example, inequalities are drastically deepening, public services are reaching the point of collapse and the cost of living is rising exponentially. The everyday feels bleak and hopeless for many, and this turbulence is the backdrop to Heavy Water’s engagement with archives and collections, as seemingly disparate and unconnected events are researched, deconstructed and reformed to generate insightful constellations that map out the path of interconnected destructions through time, in order to retrace the forgotten voices of the past and locate speculative futures.

Victoria Lucas has so far sourced and researched historical items relating to witchcraft and witch-hunting; childbirth and midwifery practices; folklore and ritual; British imperialism; appropriated mythological symbols; the advent of land enclosures and processes of land extraction. Casting a wide net across interrelated subject matter gathers together specific events that, collectively, speak of what she terms intersectional colonialism; of bodies, of lands, of communities, of cultures. Maud Haya-Baviera has so far re-interpreted items relating to tourism, the exploitation of the land and the living, and war. Her artistic responses to these artefacts translate a resistance to view the world in pessimistic terms, and offers — if not a sense of hope — a way to connect emotionally and creatively with past and present realities. Joanna Whittle has referred to the Protestant Reformation as a point of bifurcation of faith and political ideology, which is then hinged with similar fissures of turmoil in periods of war. Her research into sources relating to religions, mourning rituals, archeology, material culture and war creates new mythologies woven from religious texts, poetry, war correspondence publications, romantic landscape tropes and mapped topographies.

The Heavy Water methodology begins with the archive itself. Each artist looks for the residue of the unusual and obscure — items that have washed up from a different time — cultural strata packed away in boxes and on shelves and quietly gathering dust. In this sense, the Heavy Water Collective are able to negate established institutional categories assigned to archives and collections, pulling together objects that have seemingly disparate origins and histories. New aggregates and constellations are developed through the works made, which take shape outside of the mainstream classification schemes widely used to categorise matter. In this way, the resulting body of research is separated out from the influence of the often outdated structures encountered. The Dewey Decimal System, for example, was founded by Melvil Dewey; a well known misogynist, racist, anti-semite, educator and librarian. Dewey, who was repeatedly accused of sexual harassment by his female co-workers, is credited for the ordering the vast majority of our knowledge and history. So what does that mean for women’s histories? Where is value placed, and what barriers does this create?

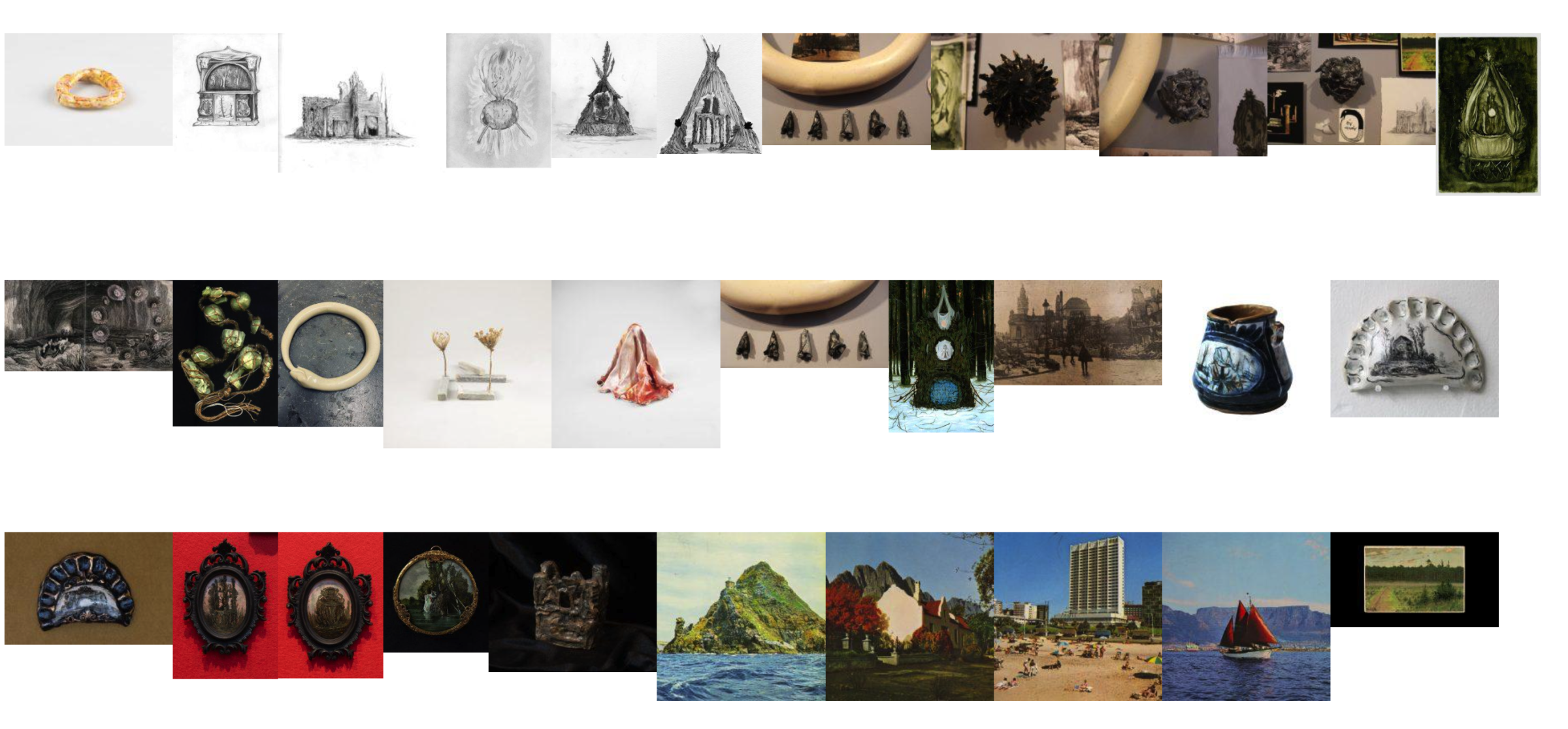

Digitised archival content and catalogue listings of archived items are examined at length, which then informs physical visits to sites in which sources are engaged first-hand. The physical encounter with each artefact is often documented through photography, scanning, sketching and recording, and these images and notes are referred to and / or incorporated in the methods developed in the artists’ studios. Each member of the collective approaches their respective research and / or reconnaissance independently. It is not until presenting findings through the website, via publications and presentations, or through curatorial projects and exhibitions, that the creative output is placed in the collective arena. As a result of this methodology, the artworks generated by the three artists maintain artistic integrity, avoiding a homogenization of practice and output. In pooling individual findings, three independent voices then speak as part of a whole. It is each collective member’s distinctive approach to making that generates further insight; in much the same way as a selection of unrelated artworks or artefacts might communicate in museological arenas of display. It is thus through their organisation of visual material, developed in response to the same collection or archive, that an emergence of new conversations, interrelations and threads of discussion manifest.

As an artistic researcher, Victoria Lucas interrogates ‘how nature is constructed, and how the concept of nature in turn constructs our political and social imaginary, with a particular focus on how gender is produced, reinforced and can be undermined through the self-representation of women within the landscape’ (Velvick, 2023). She believes that philosophical posthumanist re-immersions with our environment have the potential to “move [us] beyond the horizon of the present” moment, through concepts that “can supply us with the provocation to think otherwise, to become otherwise” (Neimanis and Loewen-Walker, 2014). The methods tested by Lucas hold a number of material components — including video, digital imagery, performance, sculpture, sound — which work together to form an aggregation of reconstituted material. Matter is entangled through the use of technological conspirators for example, as the violence of extraction is re-enacted in a way that reclaims the exploitative structures that Lucas critiques. The boundaries of material things are pushed and tested, and these processes of material destabilisation form an interrogation of the past through the materiality of the archival artefacts encountered. For example, An Account of the Voyages (2022) is a series of digital works that expose ruptures in the fabric of illustrations extracted from a 1773 account of British colonisation. British depictions of these historic encounters with indigenous communities across the Southern Hemisphere are torn apart though the glitch of the scanning method undertaken by Lucas, creating space in-between the pixels for new narratives, perspectives, and posthumanist becomings to emerge.

Maud Haya-Baviera’s practice-led methodology is one of intuitive and playful production. She employs methods that draw upon experimental artistic traditions as a way to generate empathetic responses, including photographic collages, filmmaking, sculpture and sound production. For the research conducted at Sheffield General Cemetery, Haya-Baviera refers to the original architectural design of the site, which was itself inspired by Romantic stylisations and borrowed iconography from a variety of countries and cultures viewed as exotic. In the work If Only Rome (2023), a series of five digital collages, Haya-Baviera investigates the phenomenon of cultural appropriation by creating intimate illuminations, which through their fragmentation evoke a sense of both presence and vacancy — a sense of loss — all of which respond to past architectural practices and to a wider context of globalisation in which the commodification of culture is a way to generate economic gain (Cherid, 2021). Another method employed is exemplified by the video work Beyond The Woods (2023). The work is composed of voiced letters written by soldiers, archival postcards and landscape paintings from war zones and USSR brochures, sourced during a Heavy Water Residency at the Special Collections at Cardiff University. The intention beyond this process was to create an emotional, a‑temporal and a‑geographical account of conflict. The resulting work is pensive and delicate; grave yet affirmative.

Joanna Whittle approaches her research through a transitional practice of investigative composite drawing, in which several sources are drawn together to create new mythologies. For example, from the Special Collections at Cardiff University she integrated sources from Protestant Reformation texts with reportage for the First World War, prints of Paul Nash and the war poetry of Richard Adlington. These were woven into a narrative mesh of bucolic and romantic English landscapes as an underlying and speculative setting for the artworks, providing a backdrop for this mise-en-scène in which figures move between the temporality that once confined them. From this point of embarkation Whittle goes on to create both paintings, postcard works and ceramic artefacts. Her approach is holistically phenomenological, whereby she creates new mythologies from the assumed fact of experience; assuming that archival material is a direct physical residue of lived experience. Combined with this she equally both researches and creates from a Heideggerian positionality, in which her search incorporates his theory of Abgrund where an absence of ground signifies a time of destitution, perpetuated by its concealment. Joanna’s search into the materiality of archives represents an attempt to uncover this void, in the way that one tears holes in layered handbills to find the words and worlds beneath, enabling layered histories to exist contemporaneously.

Subsequent curatorial methods act as a process of re-imagining, re-assembling and revealing histories through the arrangements established, often in the context of the gallery or museum. The boundaries between research, production and curation become porous, replicating the messy liquidity of history and the impossibility of categorization as a solidification of truth. If we look at the display case currently presented as a part of the PostNatures exhibition in Graves Gallery, for example, we see memorial ribbons depicting fragments of gravestones positioned next to a digitally ruptured visual critique of colonialist discovery. There’s a witches ladder embellished with carved amulets positioned next to constructions of religious iconography, re-appropriated Greek Mythology and re-articulated war imagery. Collectively, these works highlight the erasure of indigenous knowledge in both the UK and overseas in the name of capitalist growth. They speak of essentialist power, of humanist destruction, and of the aftermath of this violence. They interrogate humans’ need for ritual and remembrance, while sifting through the materiality of being and what that might mean in the context of an ecological crisis. This body of artistic research conveys the fact that humans are materially enmeshed with their surroundings, through the beauty and tragedy of meaning they attribute to the stuff of the world. Stone is carved to remember us in death and paint is used to translate the depth and complexity of these rituals. Tail eating snakes are transformed into an anti-capitalist omen, so that lines are drawn between the parasitic effects of Capital and the resulting ecological crisis.

In addition to curated exhibitions and museum displays, The Heavy Water collection is housed in a digital archive. Works are given accession numbers that relate to the maker and also the collection to which the artwork refers. This reassembled categorisation allows each work to exist physically, digitally and conceptually as part of a wider dialogue around how we might generate archives and re-categorize and de-colonise histories through an engagement with artefact. The archive is ordered geographically through active mapping, revealing the interrelations between site, research and object. This map, alongside archival items, will continue to be populated, so that a growing network between future and current active sites of research develops. The digital archive is live and accessible as an active resource that disrupts traditional archival models, and creates a new transferrable methodology for meaningfully engaging with archives and collections. As the Humanities face major challenges from University closures, and with a lack of political support from Central Government, this artistic research joins forces with art galleries, archives and collections, establishing a rich network with visual artists, archivists, curators, students, researchers and members of the public. Heavy Water thus forefronts the value of preserving archives for cultural heritage, public access, and for understanding our past in order to imagine a more meaningful future.

Bibliography:

‘From, At and After the Freud Museum’, in From the Freud Museum 1991 – 6 by Susan Hiller, Tate Research Publication, 2017, https://www.tate.org.uk/research/in-focus/from-the-freud-museum-susan-hiller/from-the-freud-museum, accessed 9 March 2023.

Wilson, F. and Halle, H. (1993). Mining the Museum in Grand Street, 1993, No.44 pp.155 – 172

Cherid, M I. (2021). Cultural studies, critical methodologies, 2021, Vol.21 (5), p.359 – 364